Astral Weeks by Van Morrison

Astral Weeks by Van Morrison

Morrison’s Masterpiece Revisited

Paul Szabady

July 2004

One of the stronger arguments against considering commercial popular music a genuine Art is the question of its staying power – its ability to continue to reveal new aspects over time and repeated exposure, to somehow remain inexhaustible. Its very definition almost guarantees a shallow, short-lived music, exhausted within a few listenings and then thrown away.

For a brief period in the late 1960’s and early 1970’s, however, musicians working in the pop music field attempted to break out of that superficial, throw-away mentality and tried to produce deeper works, works that could be called art by any standard. Given the congenital venal values of the music business, the emergence of this new ambition among musicians shows the power of the musical renaissance that was the 1960’s. A casual look at the roster of bands recording for Warner Bros./Reprise during this time shows just how daring even mainstream record companies were forced to become. (Van Morrison, The Mothers of Invention, Jimi Hendrix, The Beau Brummells, Pentangle, Randy Newman, Jethro Tull, Family, Neil Young, The Youngbloods, The Fugs, The Kinks, Arlo Guthrie, Pearls Before Swine, Tim Buckley, Ry Cooder, The Grateful Dead, Captain Beefheart, Little Feat, Gordon Lightfoot, Van Dyke Parks, and Joni Mitchell were just some of the acts signed to WB/Reprise at the time.)

Van Morrison was signed to Warner Bros. as the first pop artist given complete creative control of his recordings. Morrison’s previous work with Them revealed a fire and intensity as powerful as anyone on the scene: Mystic Eyes, Baby Please Don’t Go, One Two Brown Eyes, and the archetypical Gloria are as intense as Rock and Roll gets. Strongly present too was Morrison’s lyrical, melancholy, and near-poetic sensibility, focused increasingly on memories of tragically lost love. His recording of Bob Dylan’s It’s all Over Now, Baby Blue made the song his own and his 1967 Top 40 masterwork Brown-Eyed Girl, showed a potential and power that yearned to find full expression. Astral Weeks was that expression.

I discovered Van Morrison early in my musical life. Them’s Mystic Eyes literally rocketed me out of the bathtub when it first showed up on AM radio in 1965 when I was 15. The album on which it appeared was one of the first 2 albums I ever purchased. Brown Eyed Girl capped The Summer of Love in 1967, its autumnal aspect already hinting that that magic summer might never come again. Morrison then disappeared until I encountered “Astral Weeks” in the early spring of 1969, an impulse buy when college poverty kept impulse spending tightly reigned. I’ve listened to the album for 35 ears now, and I’m still discovering new aspects of it.

Recorded frantically in 2 weeks during November 1968 for Warner Bros., “Astral Weeks” is Morrison’s masterpiece. Morrison was 23 years old at the time, in transition of recording companies, in residence away from Dublin and London, and from the tortured emotional experience of watching a lover die from tuberculosis. It is very much an album of crisis: a poetic rendering of the anguish of coming to manhood, of change, alienation, growth, loss, anguish and near-madness. A deep yearning for transcendence and ecstasy permeates the album, centering on the transforming power of love. The choice of musicians for the album was inspired, particularly the propulsion of acoustic bassist Richard Davis and drummer Connie Kay. They drove Morrison’s music to a musical complexity and intensity that he was never to match during any of his later recordings, even those self-consciously jazz-tinged. Using bona fide jazz musicians (Davis was a highly revered bassist with a long solo career; Kay was drummer for The Modern Jazz Quartet) on a pop album was novel at the time; the non-amplified instruments used throughout – flute, acoustic guitars (rhythm guitar played by Morrison), harpsichord, vibes, xylophone, violin, trombone and cello – contrast strongly to the apotheosis of intensely electronic Rock and Roll occurring at the same time. Also typical of the time, the music escaped labeling. Does calling it a combination of chamber music and jazz, with lyrics poetically composed within the troubadour tradition, and sung in a combination of folk, pop, Irish and jazz styles really clarify anything?

Morrison’s main instrument on the album is his voice (he also plays rhythm acoustic guitar.) He delivers a masterpiece of virtuoso singing, the basics of which he only slightly expanded throughout his later career. Morrison has always appeared to be a very private man, a man uncomfortable in his own skin. Seeing him perform live is almost painful, so obvious is his discomfort in public performance. One senses that he is always about to explode, his rigid body language and occasional reliance on verbal musical formulas that almost appear to be nervous tics, serving to repress that potential explosion. He was near explosion during the recording of Astral Weeks, (at times over it, according to stories of breakdowns during the recording sessions,) his vocals seeming to destroy the attempts of the microphone to capture his emotional message and the meaning of his lyrics. “Astral Weeks” is an album of an artist finding his voice. Literally. Gone is the adolescent tough-punk growl of Van’s Them days, the slick vocal mask of later albums not yet formed. His singing is direct, honest and revealing: rarely has any musician revealed so truly the emotions driving his art.

Morrison’s main instrument on the album is his voice (he also plays rhythm acoustic guitar.) He delivers a masterpiece of virtuoso singing, the basics of which he only slightly expanded throughout his later career. Morrison has always appeared to be a very private man, a man uncomfortable in his own skin. Seeing him perform live is almost painful, so obvious is his discomfort in public performance. One senses that he is always about to explode, his rigid body language and occasional reliance on verbal musical formulas that almost appear to be nervous tics, serving to repress that potential explosion. He was near explosion during the recording of Astral Weeks, (at times over it, according to stories of breakdowns during the recording sessions,) his vocals seeming to destroy the attempts of the microphone to capture his emotional message and the meaning of his lyrics. “Astral Weeks” is an album of an artist finding his voice. Literally. Gone is the adolescent tough-punk growl of Van’s Them days, the slick vocal mask of later albums not yet formed. His singing is direct, honest and revealing: rarely has any musician revealed so truly the emotions driving his art.

The recording generally is quite good, better on LP than CD, better on English LP pressings than the American. The only recording glitch is Morrison’s voice: at times harsh from overloading the microphones, at times almost overwhelming from the directness and honesty of his expression. Morrison’s tendency to swallow the ends of words (my guess partly due to his native Northern Irish accent) makes some of the lyrics undecipherable, adding a level of ambiguity to lyrics that are already complex and ambiguous enough on their own. I’ve listened to the album hundreds of times, on gear ranging from the fundamental to the sublime, and there are phrases that I still haven’t been able to decode.

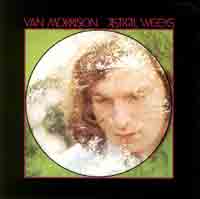

Like many artistically ambitious albums of the era, “Astral Weeks” carries the trappings of the ‘concept’ album – a united work of art painted on album-length scale. The cover photo depicts the perfect form of the Squared Circle, the mystic symbol of the union of opposites; the sacred marriage of heaven and earth. Inside the squared circle is Morrison’s melancholy face, positioned off center, looking downward and off-camera, super-imposed by branches of trees – the ‘Avenue of Trees’ that recur in two songs of the album. The 2 album sides are divided into “In the Beginning” and “Afterwards”. The individual songs are strongly lyric-based, episodically flowing with images rather than in straight linear narrative: poetic immersions into psycho-dramas drenched in memory and yearning. Their physical geography is Belfast, Dublin and London, their seasons mostly autumn and winter, the spiritual weather wet and rainy. The emotional landscape is a densely oxymoronic combination of despair and ecstasy, rage and joy, loss and revelation, alienation and affirmation, madness and mystical transcendence, pain and love.

Astral Weeks, the “In the Beginning” side’s opening song, sets a tone of strange and mysterious other-worldliness, the ‘astral’ aspect of the album. It is a declaration of alienation, of feeling rootless: “I’m nothing but a stranger in this world,” mated to a mystical yearning to be born again. “Could you find me/Would you kiss my eyes,/ Lay me Down/ In silence easy/To be born again?” Tapping a long Western mystical tradition: “I’ve got a home on high/In another world/So far away” and “In another time/In another place/ and another face:/ heaven” is most directly in tune with Theosophy, but has roots as far back as Plato and beyond. The song is so strong that I never got past it during the first 6 months I owned the album in 1969. Lovers of Into The Mystic from Morrison’s next album “Moondance” will recognize its spiritual predecessor here.

Beside You is a declaration of constancy and faithfulness to a lover facing some unnamed tragic, yet transcendent fate: “Your there on some high flying cloud/Wrapped up in your magic shroud/As ecstasy surrounds you./ This time it’s found you.” Begun with gentle acoustic guitar strumming, it appears at first to be almost a lullaby until transformed by Van’s intense virtuoso singing into a memory of anguish suffused with an almost surreal beauty. “To never ever wonder why/It has to be.”

Sweet Thing, up-tempo and exultant, re-affirms acceptance of actual physical life after the mystical longing of Astral Weeks. The singer vows to “Drink clear cool water to quench my thirst” and “To walk and talk in gardens wet with rain” and above all to “Never grow so old again.” Although the song seems addressed to a lover, the “Sweet Thing” can also be understood as an attitude to the sweetness of life itself. “And I’ll be satisfied not to read in between the lines.”

Cypress Avenue, although obviously based on some concrete geographic location in Morrison’s past, serves as a larger metaphor to some internal landscape of anguish and pain. It is the avenue of trees hinted at on the album cover, the leaves falling autumnally, one by one. “I’m caught/one more time/Up on Cypress Avenue,” “I may go crazy/Before that mansion on the hill.” “My tongue gets tied/Every, every time I try to speak” and “My insides shake/Just like a leaf on a tree.” Morrison’s delivery of these lines is as heart-rending as the experience they attempt to portray. The use of the harpsichord and violin as accompanying instruments here (the harpsichord played divinely by, I’m guessing, Van Dyke Parks) in counterpoint to Davis’ melodic acoustic bass lines is, simply, inspired. Leaving the unhinging experiences “Up on Cypress Avenue”, the singer wanders down by the railroad tracks “Where the lonesome engine drivers pine,” and is granted an almost divine epiphany: “Here come My Lady/Rainbow ribbons in her hair.” The vision is transformative: Morrison’s vision of his beloved reveals the sun in the rainy winter. Strongly echoed here is Stephan Dedalus’ epiphanic vision of a young girl in James Joyce’s “A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man,” and Dante’s first encounter with Beatrice, the figure who was to serve as his Muse and who, in The Divine Comedy, led Dante into Paradise.

The album’s second side, “Afterwards” opens with The Way Young Lovers Do, an exuberant exultation of young love. Significantly, it is the only song on the album whose season is summertime. Morrison trades scatting riffs with the trombone and the song swings and moves with an infectious élan that Morrison’s later, more sedate jazz-based song on the same theme, the autumn-set Moondance, doesn’t quite achieve.

Madame George is a mellower, nostalgic twin to Cypress Avenue of ‘In the Beginning’ and one of the more ambiguous songs Morrison has recorded. Set again on Cypress Avenue, the perspective is changed: “Down on Cypress Avenue/With the child-like vision slipping into view,” it is a song of dream, memory and leaving, focusing on the mysterious figure of Madame George. Her identity is highly perplexing: she keeps a house on “the backstreets” on Cypress Avenue: whether it is a literary salon, a bordello, or a drug den (it gets raided during the song) is highly unclear. Given the fact that Morrison’s full name is George Ivan Morrison, Madame George is also potentially a past persona of Morrison that he is leaving. “Say good-bye/To Madame George,” Morrison sings again and again in the song’s long almost mantra-like vamp, at times changing “Madame George” to “Madame Joy.”

Ballerina is again highly emotionally wrought, an entreaty to a potential lover to accept love and life “like a ballerina/stepping lightly.”

The album closes with Slim Slow Slider, a haunting, almost dirge-like recounting of an early morning meeting with an ex-lover. The song seems the least finished of the songs on the album lyrically as Morrison bluntly concludes: “I know you’re dying baby/And I know/you know it too./Every time I see you/I just don’t know what to do.”

“Astral Weeks” is Morrison’s attempt to incorporate consciously literary poetry into popular music and it is Morrison’s vocal virtuosity that allows the poetic images to work as musical lyrics. One senses that their composition was done with singing in mind. The poet Robert Graves opined that all true poetry was an invocation of the lunar White Goddess and focused on a few select themes. All true poets record their experience of her: from the medieval troubadour songs of devotion to an unattainable ‘Lady’ to Poe’s view that the greatest poetic theme was the premature death of a beautiful young woman. The common love song often reveals this invocation in an obscured form. At their most poetically evocative, love songs can be understood on more than one level: a literal song to a lover and a simultaneous invocation of all the meanings associated with The Female in our literary and psychological tradition. There is a mysterious female presence in “Astral Weeks” evoked in a variety of images that do not depend on reference to an actual female person for their evocative power. From the “barefoot virgin child’ of Beside You to the “Sugar Baby” of Sweet Thing, from the mysterious Madame George and the epiphanic “My Lady” of Cypress Avenue to the Ballerina and finally the Slim Slow Slider, the female images evoke a broad band of meaning and allusion. This allusiveness (and its elusiveness) mated with other Morrison poetic images brings an inexhaustible element to the album. “Astral Weeks” is not a throw away album.

The power of individual poetic images to reverberate within our own psyches, to bring half-realized and at times unconscious associations and meanings to light is part of the magic of poetry. Morrison’s poetic themes and images form a central core common to all of his work. Has their ever been a singer more in tune with bittersweet autumnal melancholy? Has any recorded the genuine spiritual quest of individual life and mated it with romantic love in as convincing a fashion? One of the glories of poetry and music is that it firmly resists analysis in prose and linear logic. It flies far beyond those nets. Though Morrison’s following albums – “Moondance,” “His Band and Street Choir” and “Tupelo Honey” – cemented his popular and critical success, he has never surpassed “Astral Weeks.” It remains one of the few pop albums that bears up as a true work of art, a work of bittersweet and haunting beauty.

![]()

Don’t forget to bookmark us! (CTRL-SHFT-D)

Stereo Times Masthead

Publisher/Founder

Clement Perry

Editor

Dave Thomas

Senior Editors

Frank Alles, Mike Girardi, Russell Lichter, Terry London, Moreno Mitchell, Paul Szabady, Bill Wells, Mike Wright, and Stephen Yan,

Current Contributors

David Abramson, Tim Barrall, Dave Allison, Ron Cook, Lewis Dardick, John Hoffman, Dan Secula, Don Shaulis, Greg Simmons, Eric Teh, Greg Voth, Richard Willie, Ed Van Winkle, Rob Dockery, Richard Doron, and Daveed Turek

Site Management Clement Perry

Ad Designer: Martin Perry

Be the first to comment on: Astral Weeks by Van Morrison