A Selective Sinatra Retrospective

| A Selective Sinatra Retrospective |

|

Part 1: “Only the Lonely” – Frank Sinatra and the Concept Album

|

| John B. Sprung |

| 25 September 2003 |

It is hard to believe that Frank Sinatra has been dead for five years. Just like many long-time fans, I’ve spent my entire life surrounded by his voice and still feel the creative void caused by his absence.

It is hard to believe that Frank Sinatra has been dead for five years. Just like many long-time fans, I’ve spent my entire life surrounded by his voice and still feel the creative void caused by his absence.

Think about it-Sinatra’s work made its imprint on the musical scene in the late 30’s, when All or Nothing at Allwas first heard with the Harry James Band, and continued through the surprise hits of his two “Duets” albums in the early 90’s. Imagine some other singer (before or after) having newly recorded songs on the charts in seven different decades. Most popular musicians would consider five years in the limelight a goal worth achieving, and five decades an impossibility. Paul Simon correctly observed that, “Every generation drops a hero off the pop charts.” Not so with Sinatra.

Both before and since his passing, there has been much written about Sinatra the man and Sinatra the singer.1 He, of course, was a man who inspired strong reactions among friend and foe alike. I’m not going to dwell on his having had four wives (not to mention countless paramours), his “Rat-Pack” exploits, the political odyssey from F.D.R. liberal to Reagan conservative, his non-musical achievements as a movie star, let alone his notorious Jekyll and Hyde personality. Suffice it to say, his was a larger than life existence. But I’d much prefer to focus on his major contribution to the world: his music.

Even Sinatra’s detractors are likely to admit that the man had a way with a song. But even among his fans, people align around different phases of his enduring career. These are usually segmented by record label (“The RCA Victor Years,” “The Columbia Years,” “The Capitol Years,” and “The Reprise Years.”) A close examination of his work on any of these four labels alone could find enough to defy comparison with any of his contemporaries. Even the word “contemporaries” loses meaning when assessing someone of so distinguished a musical longevity. There was literally no one who competed with him throughout his career. No one else had the creative energy.

Watching films of the young Sinatra performing can’t help but put one in mind of Jolson and Crosby. Sinatra himself gave a great deal of credit to Billie Holiday, Mabel Mercer and Tommy Dorsey for helping him shape his distinctive phrasing. Once he hit his stride in the mid-’40s, all comparisons went in the other direction. Most singers of any consequence since (including Dylan and Spingsteen) are candid in acknowledging their debt to the man the late William B. Williams dubbed the “Chairman of the Board.”

But what of new Sinatra listeners? How one envies people who are unfamiliar with his music. I invite them (as well as those of you more familiar with his oeuvre) to pull up a chair, read these words, and then listen. Somewhere post-Dylan, the notion developed that the only musicians that “counted” were singer-songwriters. As a result, singers of other people’s songs are viewed as lesser artists. Let’s face it, with rare exceptions, few singer-songwriters achieve true greatness in either category, and even fewer in both. Frank Sinatra made his living singing other people’s songs and made them (and himself) famous in the process.

We are a nation of list makers-top ten, top forty, top hundred. I (and wouldn’t be the first) could do the same with Sinatra, but that would do him an injustice, since he is not best appreciated through individual songs. I know that might sound a bit counterintuitive, particularly when (a) success is measured in gold (and platinum) records and (b) Sinatra made so many wonderful songs, each of which can stand on its own as a gem. It is, however, my belief that it was a recording innovation that enabled Sinatra to give voice to a talent that transcended the individual song. I speak, of course, of the long-playing record, which came of age precisely when Sinatra was ready to take advantage of it. While there were record albums before the advent of the LP, songs were, due to the 78 rpm format, limited to approximately three minutes in length. American Pie (the Don McLean song, not the movie soundtrack) would have filled three sides, and-as for Dylan’s eleven minute “Desolation Row,”-forget about it!

The twelve-inch LP, on the other hand, was able to yield over twenty minutes per side. What’s more, songs could now be ordered in the sequence the artist intended you to hear them. When I refer to Sinatra as the father of the concept album, I do not mean to suggest that he was the first person to record a thematically connected collection of ten or more songs. Every artist seemed to do the obligatory “Irish” or “Christmas” album. (Imagine, if you will, “Yma Sumac sings of Yuletide on the Emerald Isle.”) Sinatra, however, was aiming at mood, not location.

“Only the Lonely” was not Sinatra’s first theme album. Nor was it his first album of sad songs (look for the splendid “Close to You”). Jonathan Schwartz, radio personality and Sinatra aficionado, points to “Songs for Swinging Lovers,” as helping to define the mood of one generation much as the Beatles’ “Sgt. Pepper” did for the next. There is an ongoing debate among Sinatra fans as to whether the “real” Sinatra was the swinging (or “Ring-a-ding-dinging”) up-tempo jazz singer, or the long lost loser singing into his beer. While I think that Sinatra was great at affecting moods both bright and subdued, I find him most effective (and honest) with what he called the “Saloon Song.”

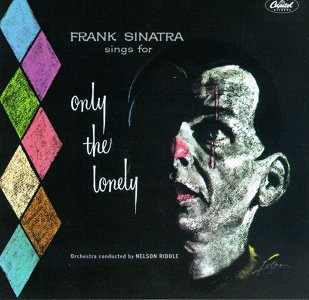

From all accounts, Sinatra the man felt things deeply and was able to express them best in songs. Despite his carefully cultivated image as a man about town, for me, the debonair playboy role seemed a bit forced, like your big brother’s tuxedo that never quite fits right. If the image of the sad clown comes to mind, nothing could provide a better segue into our featured album, “Only the Lonely.” This, both Sinatra and I agree, was his “finest hour.” Back in the days when cover art (and liner notes) were approached with the same sense of creativity as the record itself, “Only the Lonely” distinguished itself by winning the Grammy for best cover art for 1958. On it, Sinatra is portrayed in a painting as a harlequinesque clown, with his eye bisected by what appears to be a tear trickling down his painted face.

The album functions as a thematic whole, reflecting the combined talents of master arranger, Nelson Riddle (his partner on the finest of the Capitol albums), the conductor (and master violinist) Felix Slatkin, who alternated with Riddle in conducting an orchestra (depending on the session) of around 45 musicians. At the helm of this mighty ship, of course, was the vocalist, forty-three year old Frank Sinatra.

Please understand, this was not the androgynous waif whose voice ached of youth and naiveté crooning to an adoring generation of bobby-soxers. This was a man who had plummeted from the undisputed number one vocalist in the country to a lost soul, dropped by his record label, and unceremoniously dumped by Ava Gardner, the almost incomprehensibly beautiful movie star who broke up his (not so) storybook marriage. This was a Sinatra so humbled that he left a stage performance unable to sing. Rock bottom came when he was humiliated into performing novelty tunes (courtesy of hit-maker “Sing-Along-With” Mitch Miller) with a blonde bombshell comedienne named Dagmar (Jenny Lewis) and a “talking” dog. (The less said aboutMama Will Bark, the better.) If this was all that remained for him on the Columbia label that had propelled him to stardom (and for which he made millions), he could no longer record with them. Besides, neither they nor RCA wanted him.

But wait, this man, still pining for Ava, begs for the role of Maggio in the film version of “From Here to Eternity,” and wins an Oscar for his stirring portrayal. Capitol takes a chance and mates him with a young Nelson Riddle, and the two record a string of increasingly successful albums (both commercially and critically). Suddenly, he and finds himself (many years before New York, New York) back as “King of the Hill.” He has literally crawled his way back up, and will never have to descend again. The sad memories are all in the past except for one thing-he remembers what it felt like. This remembrance informs “Only the Lonely” from start to finish. As a result, you are hearing our greatest popular singer at the very top of his game.

Earlier, I described the album as a thematic whole. Let’s look at its contents2 , and as we do, bear in mind, this is not to be listened to while contemplating suicide. The thing that distinguished “Only the Lonely” from prior (and subsequent) Sinatra concept albums of sad songs on Capitol, (e.g. Close to You, Where are You?, andWhen No One Cares,) was the unrelieved despair that accompanied every song. There is not a single number that holds out any hope, so get out your handkerchiefs.3

By the way, my suggestion is that you listen to the album before you read on. When you do, it is best to do so (a) without interruption, (b) at night, and (c) accompanied only by a stiff drink. If you are fortunate enough to have the album and have a good analogue front-end (mine, I’m happy to say, rivals that of Salma Hayek’s), listen to it. If not, the re-mastered CD is of very high quality. But please, first time ’round, hold the “bonus songs.” They were not meant to be on the album. So, here we go. The songs, in original order are:

(1) “Only the Lonely,”-Cahn/Van Heusen;

(2) “Angel Eyes”- Dennis/Brent;

(3) “What’s New?”- Haggart/Burke

(4) “It’s a Lonesome Old Town”- Tobias/Kisco

(5) “Willow Weep for Me”- Ronell

(6) “Good-bye”- Jenkins

(7) “Blues in the Night”-Arlen/Mercer

(8) “Guess I’ll Hand my Tears out to Dry”- Cahn/Styne

(9) “Ebb Tide”- Maxwell/Sigman

(10) “Spring is Here”- Rogers/Hart

(11) “Gone With the Wind”-Wrubel/Magidson

(12) “One for my Baby”-Arlen/Mercer

Sinatra’s home-team writers, Sammy Cahn and Jimmy Van Heusen, commissioned the title song especially for the album. In their liner notes, Sammy Cahn writes that he found the melody so compelling, he didn’t want to change a note. As a result, he struggled to make the lyrics a perfect fit. The result is a compelling song that sets the tone for the entire album. It is a song of sad reminiscence, holding out little hope. Even if you find the one “who used to care,” and if it is the “one time that hopeless dream comes true,” and win her back, you’d best hold onto each caress, “for when it’s (love) gone you’ll know the loneliness, the heartbreak only the lonely know.” Mind you, not “if it’s gone,” but “when.” This song is a pre-rock-n-roll big brother to “Heartbreak Hotel,” and it prepares the listener for what lies at the end of lonely street.

Angel Eyes (along with One For my Baby) is one of the two classic “saloon songs” that, after the introductory theme struck by “Only the Lonely,” act as bookmarks to the album. The narrator is a jilted sport who buys the whole bar a round to help drown his sorrows at the loss of his misspent times with “Angel Eyes.” After bidding them to have fun (“the drinks and the laugh’s on me”) he excuses himself, anxious to find out who has replaced him-and why-as if the answer will make a difference. He ends with the now famous parting line, “‘Scuse me, while I disappear.”4

The Riddle arrangements and Slatkin conducting cannot be praised enough. The listener is immediately struck by the size and depth of the orchestra, which somehow never overwhelms the singer, who maintains his sense of intimacy. Although, as mentioned above, I am a die-hard analogue fan, one must compliment the mix on the compact disc, which puts Sinatra’s voice a bit more forward of the orchestra than on the LP. This increases that ineffable quality of “presence” toward which audiophiles strive.

“What’s New” addresses every jilted lover’s worst nightmare-running into your ex, and trying to maintain your poise. He’s apologetic (“probably I’m boring you”), thankful for small favors (“and you were sweet to offer your hand”). He ends again in apology: “Pardon my asking what’s new.” His last line “of course, you couldn’t know. I haven’t changed, I still love you so.” Listen to how slowly he recites those last four words. The ache Sinatra conveys is palpable. One of his legendary qualities was his breath control, which enables him to convey subtle shifts in emotion without pausing.

“It’s a Lonesome old Town, (when you’re not around)” is a first cousin to the masterful “Lonely Town” from “Where are You,” another torch album. Here as there, he’s alone. His plea is simple, consistent: “How I wish you’d come back to me.” He repeats the line as if to underscore not only the depth of his loss, but the futility of the wish.

“Willow Weep for Me,” evokes a rather simplistic metaphor. What other tree would you want by your side during a good cry? But its enveloping branches will be his only company. Corny as much of this is, I’ve always liked the imagery in the release where he asks the branches to, “whisper to the wind and say that love has sinned.” It’s not only a nice internal rhyme, but a desperate request. If seeking sympathy from a plant doesn’t qualify as the epitome of loneliness, I don’t know what would. He wants the tree as not only protection from his grief, but as an ally in passing judgment on the lover who, by deserting him, has done nothing less than causing love itself to have sinned.

This is a song (written in 1932) that sounds of another time and place, easily evoking images worthy of the antebellum South. You can hear the muted trumpet bleating out its soft Dixieland wail. Haunting as the melody is, the lyric is not particularly memorable. But that said, look what Sinatra does with it. We, too, want the tree to give him shelter from his personal storm. This song maintains the album’s thesis, that loneliness is a state of mind, and can thrive equally well in a solitary surrounding like this rural setting, or in an urban crowd (e.g. “Lonesome old Town”, “Angel Eyes”).

“Good-bye” ends the album’s first side, and remember, it was recorded as two separate LP sides of a story. While much of album is in a minor key, this song has a sonorous quality that justifies the finality of its title. The “good-bye” the couple vowed they’d never say to each other has become a reality. Lest you think Sinatra’s parting words “But we’ll go on living,” imply any optimism, he makes it clear that it is their obligation to “let love die.” When he says, “you take that high road and I’ll take the low,” we are intentionally reminded of the sentimental Scottish song “Loch Lomond,” where “me and my true love will never meet again.” But here there is no doubt that the high road of the future will be hers, while his will be the low road of loneliness and despair. His sole request, “But kiss me as you go, good-bye.” That’s the best he can hope for as Side One closes.

We turn the record over (okay, okay, I know you don’t have to flip the CD, but at least hit “pause” out of respect) to hear the most remarkable version of what most people would have thought was an overplayed, honky-tonk song. This is not your grandfather’s “Blues in the Night.” In place of the burlesque-like “bump and grind” rhythm frequently accompanying this song, the Sinatra-Riddle collaboration turns the song into the world-weary plaint Arlen and Mercer intended. In the process, it becomes a masterpiece that no other rendition even remotely approaches. Just as in “Willow Weep for Me,” the haunting presence of the muted Dixieland trumpet implicitly establishes its southern setting. Sinatra skillfully balances crescendo and diminuendo to enhance the dramatic effect. As with “Willow,” birds and nature (and here, even trains) conspire to reflect the singer’s sorrow mood. Listen to “Take my word that mockingbird will sing the saddest kind of song, he knows things are wrong and he’s so right.” Johnny Mercer, pulls off two internal rhymes plus a clever play on words. Not only is the mockingbird singing a sad song, but its very name reminds us that it is mocking the singer. Compare the sophistication of this Mercer lyric with the simplistic allusions of “Willow” and you can see the difference when the hand of a master lyricist is at work. Listen also to the restraint shown in two particular passages, where most other versions blare out the notes following “From Natchez to Mobile.” When the downbeat follows the word “Mobile” it is with soft strings, not brass. And when Sinatra sings “I’ve been in some big towns and I’ve heard me some big talk,” we know he’s not just whistling Dixie. He has been there.

As mentioned earlier, I always found his sadness more sincere than his swagger. But here, forget it. Just listen to him effortlessly ride down the musical scale when he sings “my mama was right, there’s blues in the night.” Frankie was right there, too.

In “I Guess I’ll Hang my Tears out to Dry,” both words and music make this is a beautiful exposition about a broken-hearted loser trying to get over the devastation of his lost love. The short verse is stunning in its imagery. The torch he carries is so heavy, he sympathizes with the Statue of Liberty (“I know how the lady in the harbor feels.”) Contrary to other songs on the album in which nature mirrors the mood of the downtrodden lover, here, the sun is shining and the sky is as blue as the singer’s mood. Listen to the strings ride up when he sings “Somebody said just forget about her so I gave that treatment a try. Strangely enough I got along without her, and then one day she passed me right by.” Reminds you of the poor guy in “What’s New,” who was doing all right until he ran into his former lover. The strings then let him down, like air going out of a balloon. By the last line, all that’s left of the huge orchestra is the tinkling of a lone piano. When he sighs, “Oh well, I guess I’ll hang my tears out to dry,” at least he’s trying to get over her, which is a rare move forward for this album.

“Ebb Tide” was originally an instrumental.5 At the end, Sinatra sings, “like the tide at its ebb I’m at peace in the web of your arms.” Now ebb usually means “low point,” and when something diminishes, we speak of it as “ebbing away,” Come to think of it, this isn’t even a sad song. It just sounds sad. Unless, of course, he’s just imagining the whole thing. After all, to compare the comfort of being in the arms of one’s love to “the tide at its ebb,” is an unusual metaphor. Can’t get much lower than that.

“Spring is Here,” by the incomparable Rogers and Hart, is part of a sub-genre of “Spring” songs where the promise of the season’s coming warmth exacerbates the already sad mood of the singer.6 Here the melancholy (so reflective of the sorry life of Hart the lyricist) is so heavy, the singer’s sense of loneliness is palpable. There’s nothing joyous or even remotely spring-like about the music. It’s almost funereal.

“Gone With the Wind,” can’t help but call to mind the peculiarly southern sense of loss. “I had a lifetime of heaven at my fingertips,” emphasis on had. The flame burns out, just like the torch that’s “gotta be drowned” in “One for my Baby,” the album’s closer. This perfect finale (another Arlen/Mercer collaboration) is, in my opinion, one of Sinatra’s very greatest songs. I have never heard a more balanced song. Everything in it complements its other components. The melody perfectly suits the mood of the lyric and the Riddle arrangement is sheer perfection. It is hard to imagine a better piano accompaniment than that provided by Bill Miller. The sad, spare, jazzy piano subtly alternates with the strings. No brass at all, not even a muted trumpet or woodwind until “and that’s how it goes,” when a bluesy clarinet comes in, makes a brief appearance, only to retreat in favor of the strings, which themselves bow out to the solo strains of the tinkling piano. It’s a perfect thematic bookend to “What’s New” and the end of the album.

“Only the Lonely” was a carefully thought through project, and was meant to end here. “Sleep Warm” and “Where or When” (included on the CD) were never recorded to be part of the album. This is not meant as a criticism of the songs themselves, although neither of them would likely have been included on the album. “Sleep Warm” is a pleasantly harmless lullaby, lacking even a hint of the gloom that pervades “Lonely.” “Where or When,” on the other hand, is a superb rendition of a song that Sinatra went on to spend the rest of his career ruining as an up-tempo finger snapper. This version goes down as one of his greatest ballads, but is more about the déjà vu of true love than the loss that is the sine qua non of the album.

One last thought about what might have been. The sophisticated “Lush Life” was meant to be part of this album. According to “Sinatra 101,” by Ed O’Brien and Robert Wilson, Sinatra tried it on one of the overloaded sessions when arranger Nelson Riddle was away on tour with Nat “King” Cole. I have heard one of the three takes, after which Sinatra agrees with someone’s suggestion to “put it away for a while.” He adds, “Yeah, put it away for about a year.” Too bad. It is a great song that few people can sing, but I believe Sinatra would have mastered it.7

So there you have it, “Only the Lonely.” Hopefully, you followed my suggestion to listen to it before reading this piece. Now I would suggest you give it another listen and tell me what you think. Like good wine, “Only the Lonely” improves with each tasting. Savor it.

FOOTNOTES

1 These were the last words Sinatra sang before he began his short-lived retirement in 1971, inspired by a sense of despair that his kind of songs were no longer being written.

2 The post-mortem selection ranges from a semi-philosophical tome by Pete Hamill called “Why Sinatra Matters,” to the latest in a succession of “tell-all” books by the great man’s former valet. Now those who care can learn how specially designed undergarments concealed one of his most formidable assets. Next year look out for the children’s Christmas book, “Frank Sinatra-electric train engineer extraordinaire.” (Although he was a renowned collector of model trains, I hope I’m just kidding).

3 As a technical note, we are looking at the songs that comprised the original LP. The original Capitol monaural recording contained twelve songs. (Actually, there was to have been a 13th; but more about that later.) The stereo version dropped two numbers, “It’s a Lonesome old Town” and “Spring is Here.” There seems no plausible explanation for this other than the added groove width required on early stereo recording. A complete stereo version didn’t come out for many years, until an English pressing from EMI was issued under the title, “One for My Baby.” In addition to owning all of the above, I am most fortunate in having the Mobile Fidelity half-speed master recording in stereo, as part of their wonderful box set of Sinatra Capitol LPs. When the CD came out in the mid-80’s, it included two “bonus”” songs, in addition to the original twelve. In a concept album, as we shall see, adding songs can be as problematic as eliminating them. Simply stated, the recording becomes something other than what the artist, arranger, and producer intended. Just as with the bonus of “deleted scenes” and “alternate endings,” there are artistic reasons why they were not included.

4 In the liner notes to the EMI LP, (called “One for my Baby,” but containing all twelve of the “Only the Lonely” numbers), Stan Britt writes that Nelson Riddle told him he finished his final chart just after his mother died following a lingering illness. In “The Song is You,” Will Friedwald’s seminal book on Sinatra, the author relates a similarly story, adding the fact that Riddle’s young daughter’s died shortly before he began charting “Only the Lonely.” These two tragic events understandably darkened the already somber tone required by the songs. “Smiley Smile” it’s not.

5 In 1953, The Robert Maxwell composition was made into a hit by Frank Chadfield. When the lyrics were subsequently added, Sinatra (and later the Righteous Brothers”) picked up on it. As with “Moonlight Serenade” and other instrumentals to which words were tacked on after the instrumental became a hit, it’s not always an easy thing to make it sound natural. Here, the Carl Sigman words are skillfully matched to the music, with the lushness of the harp and strings mirroring the sound of the waves.

6 e.g,. “Spring will be a Little Late this year,” “Spring can Really Hang you up the Most.” Even the fellow with premature Spring Fever in “It Might as Well be Spring” is “feeling kind of gay in a melancholy way.”).

7 We tend to think of “lush” as a synonym for “posh.” Here, the “Lush Life” is the life of a, well, lush. This song would have worked perfectly as a third saloon song with “Angel Eyes” and “One for my Baby.” The Nat Cole version is good, but not great. Linda Rondstadt, who did some wonderful stuff in her three-album salute to the Sinatra-Riddle collaborations, tried her hand at “Lush Life.” Unfortunately, for someone whose country, rock, and Mexican songs include some of the most accomplished pop singing of her generation, she just didn’t seem to understand the lyric in the way Sinatra would have had he stuck it out. He possessed the rare gift of making us believe he knew what he was singing about. On those rare instances when he didn’t seem to get it (e.g. “Mrs. Robinson,” “Both Sides Now”), it stuck out like the proverbial sore thumb. Interestingly, when Jonathan Schwartz put together a Sinatra tribute in honor of his 80th birthday, even with Rondstadt on the program, the late Rosemary Clooney was chosen to sing “Lush Life.” Since the evening consisted entirely of songs associated with Sinatra, there was something special about her “completing” his most famous unfinished song. While her voice may not have been what it was, she understood the song and sang it masterfully. Frank, that one was for you. And Nelson Riddle.

![]()

Don’t forget to bookmark us! (CTRL-SHFT-D)

Stereo Times Masthead

Publisher/Founder

Clement Perry

Editor

Dave Thomas

Senior Editors

Frank Alles, Mike Girardi, Russell Lichter, Terry London, Moreno Mitchell, Paul Szabady, Bill Wells, Mike Wright, and Stephen Yan,

Current Contributors

David Abramson, Tim Barrall, Dave Allison, Ron Cook, Lewis Dardick, John Hoffman, Dan Secula, Don Shaulis, Greg Simmons, Eric Teh, Greg Voth, Richard Willie, Ed Van Winkle, Rob Dockery, Richard Doran, and Daveed Turek

Site Management Clement Perry

Ad Designer: Martin Perry

Be the first to comment on: A Selective Sinatra Retrospective