LessLoss Anchorwave XLR Interconnect

| LessLoss Anchorwave XLR Interconnect |

| Anchor’s Aweigh! |

|

|

|

October, 2011 |

I’ve owned a number of commercial RCA interconnect cables over the years—Cardas, Nordost and few economy brands—but I’ve mostly made my own cables from RG59/U coax and, when I transitioned to balanced, Belden 1800F. I once made a pair of RCA interconnects using two lengths of hookup wire spaced about one inch parallel, held by two layers clear packing tape. No shield. Vanishingly low parallel capacitance. Presumably not even remotely close to the 75-Ohm characteristic impedance of RCA connectors. A radical experiment at the time—which I guess must have succeeded because the friend to whom I gave them kept them in his system for years. There is indeed more than one way to make an interconnect, and when one wanders into the pricier sort of cables there’s often extensive documentation of theory and execution—intended to prove that theirs is the exclusive and best way of going about it. To the uninitiated reading the advertisements, it might seem that each and every cable, from the sub-$100 utility job to the super-$1000 luxury model, is the very best. In fact, there are many good cables around, but ultimately it’s a subjective matter, and preference cannot be explained by theory of design. I knew a guy who could not stand the sound of Nordost cables, and at the time I was using their cables in my system and found them very musical (as well as very appealing in theory).

Of course some theories are more palatable—make more sense—than others, though there is a risk in dismissing a speculation merely because it doesn’t make sense. A lot of physics theory over the past hundred years, particularly particle physics, doesn’t make sense but is nonetheless factual. And the theoretical is an area where I’ve always found LessLoss products particularly interesting and intriguing. The Anchorwave cable is in that lineage.

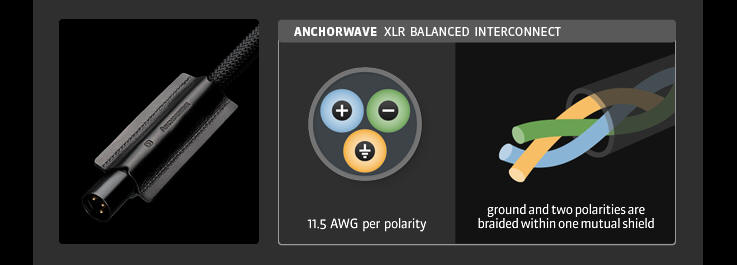

The first thing that strikes one visually are the leather “cuffs” on the XLR connectors, certainly not to everyone’s taste. They contain branding and, in the case of the unbalanced version, directional information. They do make it somewhat easier to pull the connectors, but they can also can make chassis connections a bit crowded. A quibble to be sure. The next thing that strikes one is the sheer diameter and heft of the cables: each leg is 11.5 gauge (ampacity ~25A), a heavier gauge than many power cords! The XLR version contains three of these thick wires wrapped in an attractive black woven synthetic. The RCA version contains two wires. And the loudspeaker cable contains a pair of 9 gauge versions of these wires (ampacity ~40A).

Common sense tells you that a cable intended to carry a few milliamperes—any signal cable—need not be robust. (Loudspeaker cables on the other hand may have to handle peak currents of many amperes.)Indeed, I’ve seen interconnect cables that proudly proclaim the advantages of using a single, thin strand of wire. But Anchorwave wire is, as I pointed out, very robust indeed. The wire making up a single conductor consists of 196mono-crystal strands of copper; each strand has a thin coating of insulation, which is what makes it litz wire. Litz (from the German “litzendraht” meaning ‘many-stranded’) was invented by Nicola Tesla and its raison d’être is improvement in the conduction of alternating current by the reduction of eddy currents which cause skin and proximity effects.

One of the few topics on which most cable manufacturers will agree is that low inductance and low capacitance are generally desirable. Based on their design, I presume Anchorwaves too have low unit values of inductance (L) and capacitance (C). How be it, the LessLoss web page qualifies this viewpoint, noting that values of L and C become significant at audio frequencies only at cable lengths far greater than those found in home stereos. Two home audio cables having totally different design philosophies may both sound excellent, but at lengths of a few feet, higher values of C and L in the one, and lower values in the other, will of themselves have no audible consequences. No, the philosophy behind the Anchorwave design centers around low resistance, reduced eddy currents, sophisticated shielding and vibration control.

Of course the ultimate test of whether a design is successful is in the auditioning, but LessLoss went further and programmed a computer to generate visual models using traditional Maxwellian electromagnetic theory, in order to see how cable configuration and materials relate to current flow and electromagnetic fields, and how this in turn relates to sound quality. The massive calculations involved revealed two salient points: current dispersion within a given conductor is dependent on the number of, and geometry of, all the conductors arrayed with it. It is intuitively obvious that the more strands, the less actual current flow each strand has to handle. But what’s actually happening in a conductor with an applied voltage is a good deal more complex (and a good deal more interesting) than electrons bumping one another out of orbit like infinitesimally small, caroming billiard balls. However the billiard ball analogy is adequate to the occasion: ideally, the density of “billiard balls” is evenly distributed in a cross-section of a conductor. In reality it is not—and different cable configurations can be closer to, or farther away from, that ideal. That is why the Anchorwave uses multiple litz strands, because of what they do to the theoretical current distribution. And real world auditioning of numerous experimental designs bore out a correlation between theoretical current dispersion and sound quality.

Litz wire has another advantage. Cupric oxide (CuO), unlike silver oxide (Ag2O), has semiconducting properties and its formation on copper wire even inside plastic insulation really can occur; how readily depends on the quality of the insulation and outer jacket as well as other factors. Cupric oxides on the surface of copper wire result in “diode effects” due to “strand jumping.” This is a potential source of noise that can pollute the signal. Litz wire, because each strand is coated with a durable, adhering layer of insulation, obviates this possibility. No oxidation, no strand jumping. I’ve seen decades-old enameled wire with nary a sign of oxidation; and I’ve seen quality fine-stranded, high-purity copper wire corroded despite being inside a heavy plastic jacket.

Surrounding the Anchorwave litz bundle is a tightly woven synthetic cloth tube that is designed to filter frequencies in the 10MHz to 20GHz range (70-85dB down). The fibers making up this serving are complex and provide that extraordinarily wide bandwidth. Each fiber consists of a core polyester monofilament, wrapped in concentric layers of nickel, copper, nickel, and nickel cobalt alloy. The frequency range of this shield is specifically designed to fall far above the audible spectrum; LessLoss feels this produces superior sound quality by not restricting audio frequencies, while at the same time protecting the signal from the audible byproducts of HF-SHF contamination.

Unlike traditional foil or woven/stranded wire shielding, this woven synthetic material is non-capacitive at audio frequencies, which will result in less coloration than traditional shielding methods. Audio frequencies see, in effect, no shield at all, no capacitance (which theoretically can roll off highs), no induced or stored energy (which can cause time smear), and no distortion of the signal’s electromagnetic field. Around this shield is a polyolefin cover that seals the bundle against moisture and chemical contamination. And finally an outer cover made of cross-braided polyethylene terephthalate (PET) which is a durable and abrasion resistant woven material.

Common sense also tells you that a high mechanical damping factor is desirable. Vibration in audio equipment tends to find a way of making its presence audible. The literature is replete with references to ways of controlling vibration, whether you’re reading about cables, cones, capacitors or AC outlets, whether the problem is capacitive and inductive fluctuation or micro-arcing. The Anchorwave uses a singularly ingenious system to damp vibrations. There is a relatively thick fill of 12-44 micron particles between the litz bundle and the shielding cloth, and because the particles are amorphous there is no likelihood of a lattice forming which could transmit vibrations. Indeed, these cables have a hand-feel unlike any other wire. As an analogy, think of the damping properties of a thick layer of sand. Vibrations, shock, impact, all converted instantly to friction/heat. No vibrations, no reverberation. In normal use I don’t see there being a problem of the nano-particles “drifting,” resulting in an eccentric litz bundle. I suspect one would have to deliberately mishandle the cable repeatedly to bring this about, and even then I’m not sure some eccentricity would lessen the overall damping properties of the design.

Loudspeaker cables are outside the purview of this review, but it is noteworthy that there are demonstrable as well as theoretical electrical advantages to Anchorwave’s heavy gauge. In the connection between amplifier and loudspeaker, resistance is significant. At the amplifier end this is usually expressed as damping factor, which is inversely proportional to the internal resistance of the amplifier output stage. The lower the resistance, the higher the damping factor, the better. Damping is ultimately about physical control of the woofer cone during large excursions: a lower resistance cable will provide superior damping, superior control of cone inertia by the amplifier, and therefore superior bass clarity and more realistic transients. And since resistivity is inversely proportional to conductor cross-sectional area, thicker cable provides a higher damping factor.

Clifford Jordan: Live at Ethell’s(Mapleshade 56292). I did not find glaring differences between my current reference interconnects (Wywires) and the LessLoss Anchorwaves; certainly nothing approaching the sort of differences I heard comparing my current and previous (Neutrik/Belden) reference cables. Both Wywires and Anchorwaves are well thought out, but thought out along very different lines. They both make remarkably good music and, serendipitously, they are priced within a few dollars of each other ($849, $843). But there are clear if subtle differences, and I opted to use a few well known test CDs in order to pin down those differences more readily. This particular old war horse of a CD has seen much duty in these pages, and it remains a very apt candidate to reveal small differences in such imponderables as presence, imaging and sound stage.

Clifford Jordan: Live at Ethell’s(Mapleshade 56292). I did not find glaring differences between my current reference interconnects (Wywires) and the LessLoss Anchorwaves; certainly nothing approaching the sort of differences I heard comparing my current and previous (Neutrik/Belden) reference cables. Both Wywires and Anchorwaves are well thought out, but thought out along very different lines. They both make remarkably good music and, serendipitously, they are priced within a few dollars of each other ($849, $843). But there are clear if subtle differences, and I opted to use a few well known test CDs in order to pin down those differences more readily. This particular old war horse of a CD has seen much duty in these pages, and it remains a very apt candidate to reveal small differences in such imponderables as presence, imaging and sound stage.

Presence really is an imponderable, since it can sometimes be experienced under distinctly low-fidelity conditions. It would seem to be made up of numerous qualities, yet it remains elusive. We all recognize it and cherish it, even as we struggle to describe it. By imaging I mean the precision of delineation and locus of instruments and singers. The term is associated with reproduced music, but I think it can be applied to live music. Close your eyes in a poorly designed concert hall: the tone and dynamics may be spine tingling, but the image will be muddy and will vary depending on where you sit. I’ve certainly been at concerts where “imaging” was a muddle. This is part of the reason concert halls have reputations. By sound stage I simply mean width of the image. An orchestra should appear big, a piano should appear relatively small (all, of course, depending on microphone placement and mastering). Piano recordings can be notorious for an unrealistically wide sound stage. Both imaging and sound stage are dependent on venue, but few of us are able to construct a dedicated room along acoustically ideal lines. Some of us are quite limited even in the placement of room treatments and loudspeakers.

The Achorwave presents a large soundstage with a great deal of detail. The players are “here,” right up front. There is an undeniable excitement and immediacy. Along with this strong sense of presence are all the nuances of the performers’ technique and instrumental details. This is a different image than that presented by my reference cables, which is slightly more compact, somewhat further back behind the loudspeakers with a correspondingly slightly smaller sound stage. The Wywires are intimate too, but in a more laid back fashion. I felt there was something of a predominance of image precision (Wywires) compared with a keener, tactile sense of presence (LessLoss). This is not to imply that either cable is “lacking.” In fact both do such an excellent job I sometimes felt like I was making verbal mountains of perceptual mole hills. I liked both of these presentations very much, found them both convincing and involving.

Beethoven, Piano Sonata No. 15,Gerard Willems (ABC Classics 465 695-2). My review of Gerard Willems’ complete Beethoven piano sonatas goes into some detail about the mechanical innovation that sets the Stuart & Sons piano apart. Stuart’s innovativeagraffe—the mechanism that secures the strings at the bridge—enables a vibrating string to remain in the vertical plane so it vibrates longer, and with a richer harmonic profile. Also the absence of any lateral tension on the bridge enables them to use a thinner soundboard, which in turn will have better transient response and be more lively and harmonically complex.

Beethoven, Piano Sonata No. 15,Gerard Willems (ABC Classics 465 695-2). My review of Gerard Willems’ complete Beethoven piano sonatas goes into some detail about the mechanical innovation that sets the Stuart & Sons piano apart. Stuart’s innovativeagraffe—the mechanism that secures the strings at the bridge—enables a vibrating string to remain in the vertical plane so it vibrates longer, and with a richer harmonic profile. Also the absence of any lateral tension on the bridge enables them to use a thinner soundboard, which in turn will have better transient response and be more lively and harmonically complex.

This one is also a tough call. Again there is no “winner” between the two cables, only a similar difference in presentation. The Anchorwave is very detailed, and talk about nuances: even the nuances have nuances. I have the impression I am sensing details that may not even be fully conscious. Perhaps, since trade-offs are part of any design, there is no “perfection,” only different flavors of accuracy. Different cables may simply have different characters, stress different aspects of the sound. The Anchorwave presents a striking image, very solid and palpable. The ambience of the piano interior, it’s mechanism and materials are incisively portrayed. My reference cable again is a bit more laid back and more oriented to studio ambiance; the “image,” the sense of locus, is set further back. Rather than presenting a tangible piano filling my living room, the reference presents a sense of a piano in its own venue. Adjectives that spring to mind for the Anchorwaves are “exciting,” “dynamic,” “tactile,” and “detailed.” It has great weight and authority. And since I do not know the actual microphone setup and venue acoustics, the question of which image is closer to the original venue must remain unanswered. Again, I find both presentations convincing and involving.

Nojima Plays Ravel, Minoru Nojima (Reference Recordings RR-35CD). I have used this as a test CD not only because it is particularly fine but also because I had a description of the recording setup from Keith O. Johnson, who engineered it. This is the only piano recording I know that definitely was not close mic’d. The Anchorwaves bring out the real goods here, the richness and delicacy of the tone, the snap and rumble of the bass strings, and the clear image of a piano some fifteen or twenty feet behind the loudspeakers. This is the best sound and the most finely traced image from this CD I have heard. It is singularly thrilling.

Nojima Plays Ravel, Minoru Nojima (Reference Recordings RR-35CD). I have used this as a test CD not only because it is particularly fine but also because I had a description of the recording setup from Keith O. Johnson, who engineered it. This is the only piano recording I know that definitely was not close mic’d. The Anchorwaves bring out the real goods here, the richness and delicacy of the tone, the snap and rumble of the bass strings, and the clear image of a piano some fifteen or twenty feet behind the loudspeakers. This is the best sound and the most finely traced image from this CD I have heard. It is singularly thrilling.

The time I have spent with the Anchorwaves has been interesting and rewarding. Interesting because of the meticulous theoretical research that has gone into construction and materials; I continue to be fascinated by the ingenious technological developments in our hobby. And rewarding for the image accuracy, dynamics and sheer musicality it brings to my system. Considering the complexity and quality of the Anchorwave design, I was actually surprised at how reasonable the price is. Highly recommended.

![]()

LessLoss Anchorwave XLR Interconnects

Price: $784/pair

Contact:

LessLoss Audio

1 Polk Street Unit 1703

San Francisco, CA 94102

Website: www.lessloss.com

Phone:

USA: +1 (310) 801-7089

![]()

Don’t forget to bookmark us! (CTRL-SHFT-D)

Stereo Times Masthead

Publisher/Founder

Clement Perry

Editor

Dave Thomas

Senior Editors

Frank Alles, Mike Girardi, Russell Lichter, Terry London, Moreno Mitchell, Paul Szabady, Bill Wells, Mike Wright, and Stephen Yan,

Current Contributors

David Abramson, Tim Barrall, Dave Allison, Ron Cook, Lewis Dardick, John Hoffman, Dan Secula, Don Shaulis, Greg Simmons, Eric Teh, Greg Voth, Richard Willie, Ed Van Winkle, Rob Dockery, Richard Doron, and Daveed Turek

Site Management Clement Perry

Ad Designer: Martin Perry

Be the first to comment on: LessLoss Anchorwave XLR Interconnect